This Article is written by Aditi Dubey of Soa National Institute of Law.

“Article 136 is not a general appeal but a special jurisdiction for special justice.”

– Supreme Court in Pritam Singh (1950)

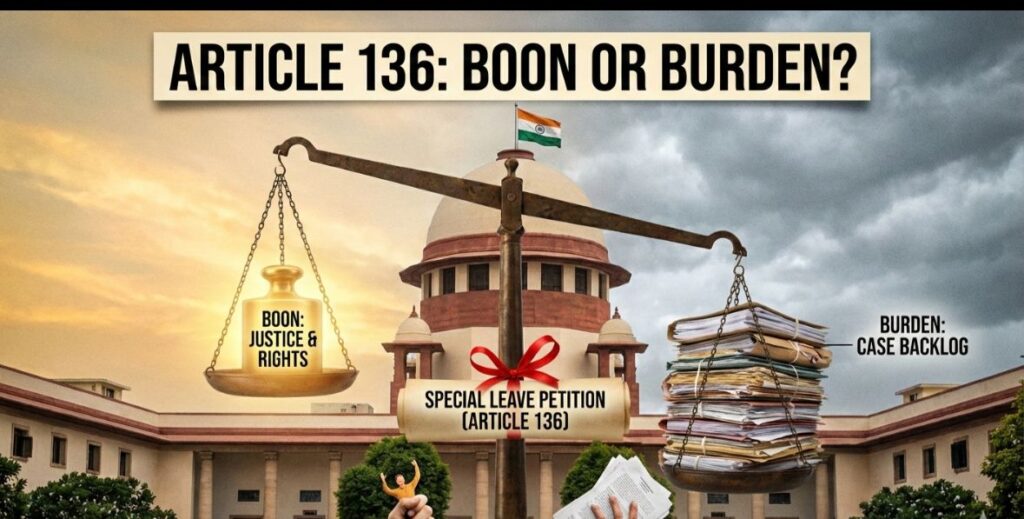

One Special Leave Petition can either save justice or sink the Supreme Court under casefiles. Article 136 gives India’s apex court extraordinary power to grant special leave against any judgment from any court or tribunal across the country (except military tribunals). Murderers walk free despite ironclad evidence. An SLP can reverse it. Decades-long property battles? SLP offers final resolution.

Designed as a rare corrective for grave injustice, Article 136 now drowns in routine litigation. Lawyers file SLPs mechanically against every High Court loss. These petitions consume over 70% of fresh Supreme Court filings, with 82,000+ cases pending the worst backlog in history. Constitutional benches waste precious time on landlord-tenant squabbles while Chief Justices warn of “judicial emergency.” From its 1935 colonial roots to today’s 2026 pendency nightmare, this discretionary powerhouse evolved from emergency savior to chronic suspect. Boon or burden? Pritam Singh demanded restraint 75 years ago, yet the flood continues unabated.

Historical Evolution

Article 136 of the Indian Constitution vests the Supreme Court with discretionary power to grant special leave to appeal (SLP) from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence, or order passed by any court or tribunal across India, except military courts.

Its traditional roots lie in Section 205 of the Government of India Act, 1935, which empowered the Federal Court to grant leave sparingly from High Courts or other tribunals. Between 1937 and 1947 only 112 appeals were filed with 48 admitted primarily federal disputes and princely state matters emphasizing selective invocation over routine access.

In the Constituent Assembly, Draft Article 112 (June 3, 1949) initially restricted civil appeals from High Courts to cases exceeding Rs 10,000 or involving princely states. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar defended unfettered discretion against “legislative rigidity,” arguing it ensures justice where none exists. K.M. Munshi supported broad access for grave injustices. The final text, adopted on October 16, 1949, imposed no monetary or substantive limits, enshrining pure judicial policy.

Judicial Development (1950s-1990s)

The Supreme Court wasted no time defining boundaries post-inauguration (January 26, 1950). Pritam Singh v. State (1950), AIR 1950 SC 169 its first major SLP dismissed a criminal appeal against Allahabad High Court, decreeing Article 136 addresses “grave injustice” only, never routine fact-review.

Dhakeswari Cotton Mills Ltd. v. CIT (1955), AIR 1955 SC 65 entrenched pure discretion: “No inexorable rule or rigid formula” governs admission. K.K. Verma v. Union of India (1954), AIR 1954 SC 571 opened direct SLP access, skipping High Court certificates. Sanwant Singh v. State of Punjab (1961), AIR 1961 SC 1971 codified grounds: perversity, jurisdictional error, public importance.

Post-Emergency, expansion accelerated. Raj Narain v. Union of India (1975), (1975) 4 SCC 428 admitted public law SLPs against Indira Gandhi’s election, kickstarting PIL synergy. S.P. Gupta v. Union of India (1981), 1981 Supp SCC 87 (First Judges Case) scrutinized constitutional appointments. L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997), (1997) 3 SCC 261 made all tribunal orders SLP-amenable, ensuring judicial supremacy. Filings rocketed: 1950s (dozens/year) -> 1970s (hundreds) -> 1990s (thousands).

Boon Aspects

Article 136 truly saves the day when lower courts make terrible mistakes. Take Rajinder Singh v. State (1997). When High Court wrongly freed a murderer despite clear eyewitnesses. The Supreme Court stepped in and convicted him properly and gave the family justice after years of pain.

In Bharti Airtel Ltd. v. Union of India (2021), (2021) 10 SCC 41, telecom companies faced bankruptcy when the government demanded ₹92,000 crore in sudden AGR dues. An SLP recalculated these liabilities fairly, preventing industry collapse and protecting millions of jobs nationwide.

The M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1988) AIR 1988 SC 1037, targeted Ganga pollution. SLPs forced Kanpur’s tanneries to shut down operations and install treatment plants, literally reviving India’s holiest river and safeguarding public health.

Bhima Koregaon (2018) gave activists fair bail hearings when lower courts kept them jailed endlessly. Tribal communities won forest lands back against powerful companies through SLPs. L. Chandra Kumar (1997) made sure unfair tribunals answer to Supreme Court.

When everything else breaks down like legal technicalities, unfair judges, boards with no appeal option ,Article 136 steps in and sorts it out. People’s rights get protected, public needs served, confidence in courts comes back. It serves as democracy’s final backup plan.

Burden/Challenges

Article 136’s unlimited power has created a massive backlog problem. SLPs now make up 70% of all new cases (over 80,000 being filed each year), with more than 50,000 cases pending; ordinary people wait 5-10 years for justice. Nearly all (95%) get rejected right at the start, but sorting through them still wastes judges’ valuable time.

Most criminal SLPs (60%) just want the Supreme Court to re-examine evidence, directly ignoring the Pritam Singh rule against this. Asian Resurfacing (2022) tried stopping repeat petitions, but people keep filing junk anyway.

This setup weakens the High Court’s final decisions and creates tension between states and center. After Chandra Kumar, tribunal cases flooded the top court. Rich people with lawyers file silly petitions that block poor citizens’ real cases. Judges spend 80% of their day just deciding which SLPs to even hear, leaving no time for important constitutional matters.

Quick verbal rejections during hearings feel unfair, no proper arguments allowed. Other countries look at India and think our Supreme Court acts like a regular trial court. All this pressure slowly destroys faith in our judiciary’s strength.

Reform Suggestions

To fix Article 136’s huge backlog without losing its strength against real wrongs, start with High Courts using a quick checklist for serious cases. This could stop 70% of useless SLPs from reaching the Supreme Court. Use a simple two-step plan: small Division Benches first check if an SLP is worth it, then send big ones to full Constitution Benches. Limit it to major legal or rights issues, no everyday murder acquittals or property fights.

Use court computers (already tested) to spot bad petitions fast. Set firm rules: decide SLPs in 6 months or drop them. Fine people who file too many to stop waste. Change the Constitution a bit to say “only special cases,” like in America. This cuts SLPs from 70% to 20% of work, letting the Supreme Court focus on what matters most without closing doors on true injustice.

Future Directions

Article 136’s future hinges on tech and structural reforms. Court systems already cut delays 30%; advance with backlog-predicting tools and special teams to redirect routine SLPs to High Courts, freeing judges for landmark cases.

By 2027, a constitutional amendment could limit SLPs to major public interest matters, banning routine acquittals. Adopt U.S.-style four-judge consensus for hearings and dedicated benches for environment, rights, and policy. Long-term, digital verified records from lower courts resolve facts upfront, turning the Supreme Court from petition mill into India’s constitutional guidepost.

Conclusion

Article 136 is a constitutional genius that went viral. Born as the Federal Court’s rare discretion, nurtured by Ambedkar’s vision and Pritam Singh’s caution, it exploded through Raj Narain’s PIL revolution and Chandra Kumar’s tribunal takeover. The payoff? Ganga flows cleaner, Airtel survives economic Armageddon, activists breathe free. But 70% of docket domination screamed crisis. 2023 certification rules and Asian Resurfacing brakes became inevitable wake-up calls. Article 136 remains democracy’s master key, now with better locks. Smart reforms like AI sorting, High Court filters and constitutional fine-tuning slash chaos while preserving power for genuine catastrophe. No Indian citizen faces final injustice. Our Supreme Court rediscovers its true calling: not a case-clearing clerk, but the Constitution’s living voice guiding seventy years toward just destiny.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Article 136 a regular appeal, right?

No, it provides extraordinary discretionary jurisdiction, not statutory appeals (Arts. 132-134). Pritam Singh v. State (1950) limits SLPs to substantial injustice where remedies fail, barring evidence reappreciation.

Can anyone file an SLP and what qualifies?

Yes, any aggrieved party against any court/tribunal judgment (except military). Sanwant Singh v. State (1961) requires perversity, errors, or public interest; K.K. Verma (1954) allows direct filing. 95% dismissed at admission.

Why has Article 136 created a pendency crisis?

SLPs rose from dozens (1950s) to 80,000+ yearly (70% of filings), post-L. Chandra Kumar (1997) including tribunals. 60% are criminal acquittals; civil disputes ignore restraints, tying up 80% of judges’ time with 50,000+ pending cases.

What reforms curb Article 136 misuse?

2023 rules require High Court certification for civil SLPs under ₹1 crore. Asian Resurfacing (2022) bans repeats without liberty; Mathai @ Joby (2020) reinforces limits. AI triage/e-filing cut delays 30%, aiming for SLPs at 20% of workload.

References

- Government of India Act, 1935, Section 205. Last visited January 26, 2026. legislation.gov.uk

- Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. VIII (June 3, 1949). Last visited January 26, 2026. constitutionofindia.net

- Supreme Court of India, M.C. Mehta v. Union of India, AIR 1988 SC 1037, available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1464877/. Last visited January 26, 2026. indiankanoon-mcmehta

- Supreme Court of India, Bharti Airtel Ltd. v. Union of India, (2021) 10 SCC 41, available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/194366952/. Last visited January 26, 2026. indiankanoon-airtel

- Supreme Court of India, Asian Resurfacing of Road Agency Pvt. Ltd. v. CBI, (2022), available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/139843982/. Last visited January 26, 2026. indiankanoon-asian

- Supreme Court of India, Mathai @ Joby v. George, (2020), available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/188549015/. Last visited January 26, 2026. indiankanoon-mathai

- NJDG e-Courts, National Judicial Data Grid – Supreme Court Statistics, available at https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/highcourts.php?state_id=1. Last visited January 26, 2026. njdg

- Devgan.in, Article 136 – Special leave to appeal by the Supreme Court, https://devgan.in/sca/article_136/. Last visited January 26, 2026. devgan

- Constitution of India.net, Article 136: Special leave to appeal by the Supreme Court, https://www.constitutionofindia.net/articles/article-136-special-leave-to-appeal-by-the-supreme-court/. Last visited January 26, 2026. constitutionofindia

- GKToday.in, Article 136, https://www.gktoday.in/article-136/. Last visited January 25, 2026. gktoday