This article is written by Neeraj Jain, Siksha O Anusandan National Institute of Law

Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023: Bridging CrPC Continuity with Modern Reforms

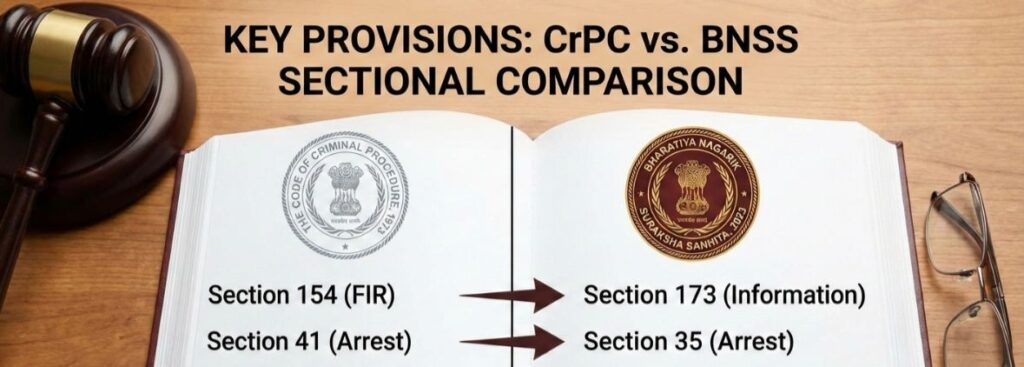

Replacing the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973, which has 484 sections compared to the 531 sections of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023 (effective as of July 1, 2024), is the BNSS. It adds technology incorporation, timelines for processes, and protection for victims but has not eradicated most CrPC designs, ensuring their continuity. In this analogy, some of the bridging elements by sectional mappings and significant changes are brought to the fore.

Background

The criminal justice system in India shifted to BNSS instead of the colonial-era CrPC so that it could solve its delays, capitalize on technology, and focus on justice to both victims and undertrials. BNSS facilitates this transition by assigning new, consecutive numbers to most CrPC provisions and replacing words such as “Code” with “Sanhita,” while integrating requirements from new legislation such as the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS). The essential bridges include compulsory electronic FIRs, forensic conditions for serious offences, and preliminary investigations on FIRs before registering offences of up to 3 years, resulting in easy adoption but limiting unfair use. This reform makes procedures relevant to current requirements, such as the availability of digital evidence and regular notifications to victims, and makes CrPC less prone to lengthy court proceedings

Sectional Mapping Overview

BNSS greatly reflects CrPC provisions but renumbers them, replaces words (e.g., “Sanhita” instead of “Code”), and updates them to reflect other current laws such as Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS). This mapping ensures a structured transition without disrupting established legal frameworks. For instance, core investigative and trial processes retain familiarity, allowing practitioners to adapt seamlessly.

Major Technological Integrations

BNSS fills the gap between CrPC and requires electronic processing of summons (Sections 63-71), searches (Section 105), and trials (Section 530). Searches/seizures (Section 105) and forensic expert involvement (Section 176) must be recorded with audio-video. These upgrades modernize the old-fashioned mechanisms of CrPC without interfering with the main flows.

In Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of U.P. (2014) 2 SCC 1, the Supreme Court mandated preliminary inquiries for certain FIRs, a principle codified in BNSS Section 173(3), enhancing technological safeguards. This integration promotes transparency in evidence collection.

Timelines and Efficiency Reforms

Delays plaguing CrPC are addressed: rape/POCSO investigations within 2 months (Section 193), daily trials (Section 346), and judgments within 30-45 days (Section 258). Promises to Sessions Courts must be fulfilled within 90-180 days (Section 232). These provisions hasten justice while retaining CrPC’s investigative structure.

For example, in Vinod Kumar v. State of Punjab (2015) 3 SCC 220, delays in trials were criticized; BNSS timelines directly respond to such judicial concerns.

Arrest, Bail, and Witness Protections

Protections for vulnerable groups remediate CrPC limitations: no arrest of persons over 60 or infirm without authorization for offences less than 3 years (Section 35); witnesses over 60 need not travel (Section 179). Section 2 expands definitions of bails and bail bonds, and electronic FIRs contribute to accessibility.

Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (2014) 8 SCC 273 emphasized avoiding unnecessary arrests, mirrored in BNSS Section 35(1). These reforms presume liberty, aligning with constitutional values.

Investigation and Evidence Safeguards

Preliminary investigations (7-14 days) prior to FIRs for offences less than 3 years help close frivolous cases, bridging CrPC Section 154’s automatic registration. Section 193 requires victim intimation of delays; e-FIRs are available 24/7. Audio-video use for evidence collection (Sections 176, 105) and compulsory forensics unify CrPC’s ad hoc practices, with chain of custody intact via digital uploads.

In State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal (1992) Supp (1) SCC 335, guidelines curbed misuse of FIRs, now statutorily reinforced

Victim and Witness Rights Enhancements

BNSS elevates victims beyond CrPC’s informant role: Section 193 demands progress reports; Section 360 grants direct hearings; Section 398 allows appeals against acquittals. Witnesses above 15/60 years receive video-conferencing or exemptions (Section 179); vulnerable identities are safeguarded. These bridges enable participation, consistent with CrPC Section 482’s inherent powers but with clearer protections.

Delhi Domestic Working Women’s Forum v. Union of India (1995) 1 SCC 14 highlighted victim rights, influencing BNSS expansions

Pleading, Trial, and Judgment Procedures

Prosecution cases will be charged electronically (Section 251); trials require day-to-day progress (Section 346), with judgments in 45 days (Section 258). Section 398 gives equal appeal powers to victims/prosecutors; Sections 413-430 unify appeal rules, where CrPC Section 482 remains under BNSS Section 528. Virtual modes (Section 530) simplify proceedings, making them less costly and time-consuming.

Mercy Petitions and Execution Protocols

Section 472 requires 30-day mercy resolutions in death penalty cases delayed over 5 years; processes may use audio-video for transparency (optional). This temporal finality, absent in CrPC, ensures humane closure. Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India (2014) 3 SCC 1 urged mercy timelines, now legislated.

Implications for Legal Practice

BNSS’s CrPC-compatible structure minimizes retraining; digital tools ease paperwork, though infrastructure lags pose challenges. Practitioners benefit from e-literacy training needs, with precedents safeguarded. Overall, BNSS connects the colonial past to a technologically advanced, time-sensitive system delivering swifter justice.

The growth of victims’ and witnesses’ rights; including regular case progress updates and appeal rights (Sections 193, 398); and better safeguards for vulnerable persons (Section 479) shifts toward a participative justice model over CrPC’s state-centric approach. It reestablishes liberty’s presumption, previously discretionary, embedding restorative justice via victim-directed forfeiture (Section 507) and forensic mandates for serious offences (Section 176).

Arrest, Bail, and Witness Protections

Protections of vulnerable groups remediate CrPC limitations: no one over 60/infirm should be arrested without authorization to less than 3-year-old offending (Section 35); a witness over 60 who is not required to travel (Section 179). In Section 2, there is an expansion of the terms of bails and bail bond, and the electronic FIRs will contribute to the accessibility.

Investigation and Evidence Safeguards

Early investigations (7-14 days) prior to FIRs concerning offenses of less than 3 years serve to close frivolous cases by bridging CrPC Section 154 automatic registration. Section 193 requires victim intimation over their delays; e-FIRs are available 24/7. The use of audio-video to collect evidence (Section 176, 105) and compulsory forensics unify the ad hoc practices in CrPC, and the chain of custody remains intact with digital uploads.

Victim and Witness Rights Enhancements

BNSS brings victims out of the level of informant that CrPC has: Section 193 demands progress reports; Section 360 grants direct hearings; Section 398 grants appeal against acquittals. This applies to witnesses above 15/60 years receiving video-conveyance or exemptions (Section 179) to sensitive identities; vulnerable identities are safeguarded. These bridges enable participation, which is consistent with the inherent powers of the Section 482 of CrPC but with clear protection.

Implications for Legal Practice

The BNSS enable practitioners to utilize the CrPC-compatible organization, which minimizes retraining and digital tools ease up paperwork, but the problem of infrastructure lags. Transitions are construed through savings clauses by the courts, which keep on going CrPC cases. All in all, BNSS serves as a connection between colonial past like and a technologically advanced time sensitive system which will deliver justice with increased speed.

Pleading, Trial, and Judgment Procedures

Prosecution cases will be charged electronically (Section 251); and trials will be required with a day-to-day progress (Section 346), judgment in 45 days (Section 258). Section 398 gives equal powers to victims/prosecutors in appeals; Section 413-430 unites the rules of appeal, where CrPC Section 482 inherently remain under BNSS reminder 528. Virtual modes (Section 530) simplify and make it less costly and time-consuming.

Conclusion

BNSS is a brilliant tapestry that pivots the strategic time-proven procedural architecture of CrPC with the pressure of the modern citizen-driven criminal justice system, providing continuity without rupture and bringing ground-breaking reforms.

The growth of the rights of the victims and the witnesses – including the requirement of regular updates on the progress of the case and the right to appeal (Sections 193, 398) and the fact that vulnerable people are now better safeguarded (Section 479) – is the shift towards the participative model of justice instead of a state-centric model, as well as the reestablishment of the presumption of liberty, which CrPC previously presupposed with discretionary rights. Additional restorative justice values are embedded in property forfeiture procedures aimed at victims (Section 507) as well as forensic requirements of severe offenses (Section 176).

Frequently Asked Questions

When did BNSS come into effect?

July 1, 2024, replacing CrPC for new cases.

Does BNSS retain CrPC’s core structure?

Yes, with renumbering and tech/timeline additions for continuity

What are the key victim rights under BNSS?

Progress reports (Section 193), appeals (Section 398), and hearings (Section 360).

Are CrPC cases affected?

No, they continue under old law (Section 531).

References

- Evidencity, “Supply chain enforcement in 2025”. https://evidencity.com/reports/supply-chain-enforcement-2025

- Industrial Cyber, “WEF sounds alarm on software supply chain vulnerabilities”. https://industrialcyber.co/news/wef-software-supply-chain-vulnerabilities-2026

- FBI Support, “Regulations Emerging to Address Software Supply Chain Security Globally”. https://www.fbi.gov/support/software-supply-chain-security-regulations-global

- WSGR Data Advisor, “SolarWinds Supply Chain Attack Legal Considerations”. https://www.wsgr.com/dataadvisor/solarwinds-supply-chain-legal-considerations

- Cohen Milstein, “MOVEit Data Breach Litigation”. https://www.cohenmilstein.com/case-study/moveit-data-breach-litigation

- SecurityScorecard, “Executive Order 14028 Strengthening Supply Chain Cybersecurity”. https://securityscorecard.com/blog/eo-14028-supply-chain-cybersecurity

- Fortress InfoSec, “EU Cyber Resilience Act Impacts Supply Chain Risk Management”. https://fortressinfosec.com/eu-cra-supply-chain-risk-management

- Cyberpeace, “Cybersecurity Threats to India’s Digital Ecosystem in 2026”. https://cyberpeace.org/india-digital-ecosystem-threats-2026

- White & Case, “2025 Upheaval to 2026 Strategy: Regulatory Risks”. https://www.whitecase.com/insights/2025-upheaval-2026-strategy-regulatory-risks

- Finite State, “Third-Party Liability in Cyber Security Law”. https://finitestate.io/third-party-liability-cyber-security-law