This Article is written by Aishwarya Jain of DES’s Shri Navalmal Firodia

Law College, Pune.

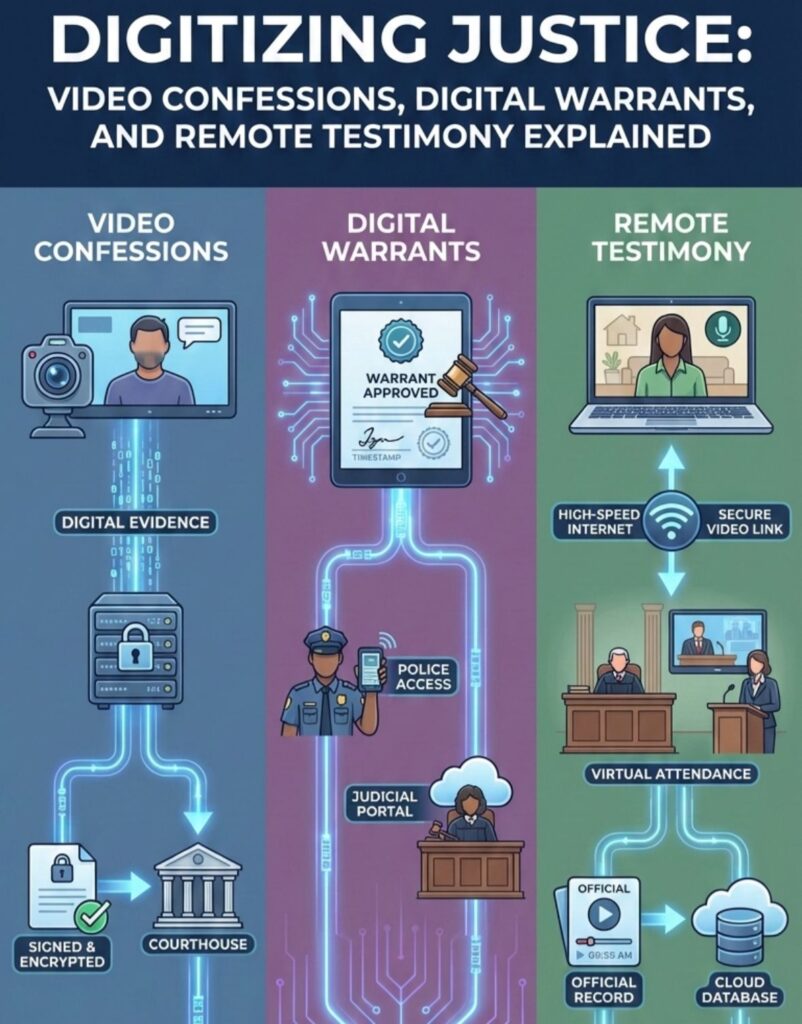

In today’s world, courts are increasingly using digital tools to handle evidence and witness

testimony. From video recorded confessions to remote testimony over video calls and from

warrants to seize electronic devices to “digital warrants”, the landscape of criminal procedure

is shifting fast. For law students and for the justice system as a whole, this raises important

questions: When is a video recording admissible? Can a witness testify from abroad over

Zoom? Do police need special orders to seize your smartphone or computer?

This article explains, in simple language, how courts in India are dealing with these

questions. We break down how video evidence gets admitted, what “digital warrants” are (or

could be), how remote testimony works and what students should watch out for.

CASE LAWS AND LEGAL DEVELOPMENTS

Here’s a look at some recent and important decisions (and legal developments) that illustrate

how Indian courts are handling video evidence, digital warrants and remote witness

testimony.

- Admissibility of Video Evidence, Supreme Court of India (2025)

The Court clarified in a September 2025 ruling that a compact disc containing a video

recording is admissible as electronic evidence, just like a document, if it is accompanied by a

valid certificate under Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. The video does not

need to be transcribed or narrated aloud by a witness in order to be admissible. In the case at

hand, which involved the seizure of contraband under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic

Substances Act, 1985, the raid was properly certified. The High Court had earlier ordered a

retrial on the ground that the video was not played during each witness’s deposition and there

was no transcript but the Supreme Court rejected this. It held that playback or transcription is

not mandatory, the video itself, when properly authenticated, is enough.

The Court stated that although the court may occasionally need clarifying or explanatory

statements (for context), this is not a general rule; rather, it depends on the facts. - Video conferences and remote testimony, High Court of Delhi (2025)

In a recent case under the Official Secrets Act, 1923 (OSA), the court permitted the

prosecution to use a secure video-conference link to record the testimony of a significant

witness who lives in the United States. The respondent court had earlier disallowed it because

it feared that classified material might be exposed.

The High Court (Single Judge bench) held that the OSA itself does not prohibit virtual

testimony, what matters is preservation of secrecy. For this specific purpose, the Court used

its authority under the applicable Video Conferencing Rules (2020) to relax some procedural

requirements (such as obtaining consent from all parties).Strict precautions were mandated by

the court, including the use of an encrypted, court-approved VC platform during camera

proceedings, turning off record or download features, watermarking sensitive documents, and

making sure that no unauthorized transmission or copying occurs. - New Law: Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS 2023), Emerging

Concept of Digital Warrants and Seizure of Electronic Evidence

With the implementation of digital procedures for locks, seizures, and evidence gathering, the

BNSS, which went into effect in July 2024, seeks to modernize criminal procedure in

India.Under BNSS (and earlier under the old code), a “search warrant” may be issued for

“any thing or document”, which courts and investigators increasingly interpret to include

digital devices (phones, laptops), electronic records (emails, chats, cloud data) and other

digital materials.

Legal commentary warns that while “digital warrants” and seizure of electronic devices are

legitimate, the courts must ensure that such warrants are not overly broad or generic.

Authorities must specify what type of data is expected and provide reasonable justification

(i.e., show why only a search of the device can yield relevant evidence).

However, if law enforcement seizes entire digital devices that contain personal information

unrelated to the case, there is worry that loosely worded warrants may violate privacy or

result in mass data collection. - Equitable Virtual Witnessing and Requirements for Remote Cross-Examination

In a different 2025 ruling, the Supreme Court emphasized that in order for cross-examination

to be fair and meaningful when witnesses testify via video conference, courts must make sure

that prior statements (such as written depositions) are sent to them electronically either before

or during testimony.

The court stated that preventing such access undermines the goal of cross-examination and

may unfairly favor or disadvantage an accused person.

WHAT ABOUT “VIDEO CONFESSIONS”?

Is a confession made on camera, during a police interrogation, automatically admissible?

Video recordings are admissible under the laws governing electronic evidence (such as

Section 65B), but only if they are properly authenticated. The person who recorded the

electronic record must provide a certificate attesting to its authenticity, lack of tampering, and

accurate reproduction of the original. A certified video confession may be admissible as

documentary evidence once it is presented to the court. The court can hear or see it, evaluate

its voluntariness and dependability, and make judgments based on the findings. It is not

automatically inadmissible just because there is no transcript or narration. This idea is

supported for videos in general by the recent Supreme Court decision.

However, certain safeguards remain important, for instance, chain of custody (to show who

recorded it, when, from what device), and assurance that the video hasn’t been edited or

manipulated. Courts often rely on metadata, expert testimony, or certification to verify

authenticity.

Also, especially sensitive areas, e.g. confessions for sexual offences or in juvenile matters,

courts may insist on additional safeguards (e.g. presence of lawyer, audio-video live

recording, prompt replay in open court).

In short, video confessions are not magic bullets, but in an era when confessions may be

captured on phone or CCTV, courts are ready to accept them, provided the procedural boxes

are checked.

CONCLUSION

Our criminal justice system is evolving, from dusty courts and paper exhibits to sealed

DVDs, encrypted links, video calls and digital warrants. Technology is no longer separate

from justice, it is becoming an integral part of how courts examine evidence and record

testimony.

While courts have started embracing video evidence, remote testimony, and the seizure of

electronic devices, these changes also require a new sensitivity to privacy, fairness and

procedural integrity.

In short, the door to “digital justice” is opening. But to walk through it responsibly, as a

lawyer, judge or student, we must keep our eyes open for both opportunity and risk.

FAQs

Q1. What exactly is a “digital warrant”? Is it different from a regular warrant?

A “digital warrant” typically refers to a warrant issued to search, seize, or access electronic

devices and data (phones, computers, cloud storage). Legally, courts have long had the power

to issue search warrants under what was earlier Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC)

and now under Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.

What’s changing is the recognition that “documents or things” can include electronic data and

devices, which means warrants can cover them. But that’s not all, the warrant must still

specify what is being sought and why. A broad, unspecified “everything on the computer”

warrant will likely be challenged.

Q2. Can any video recorded on phone or CCTV be used as evidence in court?

Not by default. Video evidence must normally be certified under Section 65B (or the relevant

law) to demonstrate that it is authentic and unaltered in order to be admitted.

Yes, the video—which includes a confession—can be used as documentary evidence if that

certification is in place and the court accepts the chain of custody and other technicalities.

Q3. Is remote testimony (witness appearing over video call) the same as in-person

testimony?

As long as specific precautions are taken, courts are currently treating remote testimony as

equivalent. For instance, in a 2025 ruling, the Delhi High Court permitted a witness from

abroad to testify via video conference in a case involving national security, provided that the

proceedings were in camera and that the link was encrypted.

In order for cross-examination to be meaningful when a witness testifies remotely, the

Supreme Court has decided that prior written statements (such as depositions) must be sent

electronically to the witness.

Q4. Are there risks or challenges with digital warrants and electronic evidence?

Yes, and students must be aware of them. Some of the key challenges:

Privacy concerns: Digital warrants, if too broad, may lead to seizure of personal data

irrelevant to the case.

Evidence tampering: Digital evidence can be altered or corrupted; courts need chain

of custody, forensic authentication, and sometimes expert testimony to ensure

integrity.

Procedural complexity: Certifying electronic records (e.g. video recordings),

preserving metadata, ensuring secure storage, all require technical expertise. Not all

courts or investigating officers may be equipped for this.

Fairness in virtual proceedings: Virtual testimony must ensure that the defence has

full opportunity for cross-examination, access to prior statements, and procedural

transparency. Courts yesterday laid down rules for this.

References