This Article is written by Tamanna, B.A. LL.B., KCC INSTITUTE OF LEGAL STUDIES AND MANAGEMENT, Gr Noida.

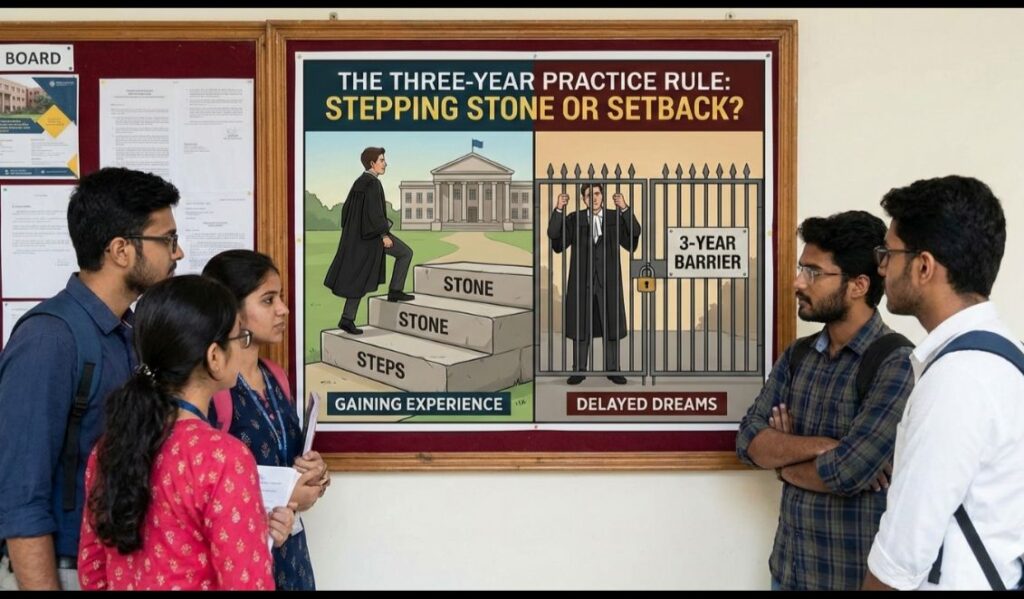

The path to becoming a judge in India, once straightforward, has become complex with the Supreme Court’s reinstatement of the three-year practice requirement for Civil Judge aspirants. This move has sparked debate- is it a step towards a more experienced judiciary, or a policy excluding talented individuals?

This article explores the issue’s history, arguments, training flaws, and potential human cost.

Analysis

The 2025 judgement has created a distinction. We need to analyze its two-sided nature – can it aid Judicial Evolution or subdue the Bar?

Arguments for the “Stepping Stone” (Pro Rule)

A judge needs practical skills and emotional intelligence that are not taught in school. The need for experience makes sure that a judicial officer has skills like cross-examination and spotting deception, which gain respect from the Bar.

- Breaking the Coaching Trap: In short, the process by which the judiciary has been examined has become a rote learning “factory” rather than a test of proper functional knowledge. By requiring prior litigation experience, we have moved away from book learning and toward experiential learning.

- The “Law Clerk” Career Path: By allowing the law clerkship to count as experience, the Supreme Court offers a solid option for those looking to become lawyers. Working with a judge at a High or Supreme Court provides great insight into the judge’s way of thinking. This experience is an excellent training ground for someone interested in law. Furthermore, a law clerkship helps link theory to practice while easing the uncertainty of earning a living from private practice.

The Argument for “Setback” (Anti-Rule)

- The Financial Barrier: A Class Divide: There should be a change in the three-year rule, which only affects the aspirants belonging to the lower middle class.” It becomes tough for them to survive if they are asked to work without pay, and the people who are already burdened with student debts. It’s like saying, “If you can’t pay for it, then you’re not meant to be a judge.” There must be a good amount for the junior advocates so they can sustain, and not just promises of exposure

- The “Fake Certificate” Culture: Fake certificates are prevalent in today’s job market, and the three-year practice requirement may exacerbate this issue. There is a major argument that it won’t guarantee actual hands-on experience, and may lead to corruption, with candidates paying for fake certificates instead of gaining real experience, thus undermining the judiciary’s integrity.

- Postponing the Dream: The three-year practice requirement may lead to burnout and uncertainty among young law graduates, pushing talented individuals to leave the judiciary for corporate jobs with better pay.

The Gendered Impact: A Structural Barrier for Women

The three-year mandatory practice requirement does not affect all aspirants equally; it disproportionately disadvantages women, reinforcing structural barriers in a profession already struggling with gender parity.

- The Timeline Trap: A woman typically completes her higher secondary education by age 18 and pursues a five-year integrated LL.B. course, graduating around age 23. Under the previous regime, she could immediately secure a job but under the current rule, she must undergo three additional years of practice. By the time she becomes eligible to even appear for the exam, she is already 26 or 27 years old.

- Women in Judiciary – A Struggle to Survive: The three-year rule is a tough pill for women in India. Marriage pressures are intense in their mid-twenties, and struggling practice makes families push for marriage over career. Litigation’s tough – safety’s a concern, amenities are lacking, and bias is there. Many talented women might drop out, hurting judiciary diversity. A stable job delays marriage, but no job means settling down. The rule’s a hurdle, costing the judiciary diversity.

- The Training Conundrum: Why Practice if Training Exists? The practice rule raises a question about India’s judicial training – If fresh graduates are “unfit” to be judges, is it because of lack of potential or failing post-selection training?

- The waiting Game: After clearing the JSE, candidates train at the state judicial academics for a year. The question arises – Why practice for three years if they’re trained for one year? If training simulated courtrooms are very effective, pre-service practice might be unnecessary.

- Quality over Quantity: Judicial training is often criticized for being academic, not practical. Trainees complain that sessions repeat law school curriculums instead of focusing on case management, digital evidence, or writing judgments.

A System Failure?

The new rule exposes a major flaw in the current system. Future judges already spend a full year in government training after passing the exam. If the government still thinks they are unprepared without three years of practice, it is admitting that its own training academies are not good enough. Instead of fixing these academies to teach real practical skills, the system is shifting the burden. It forces students to struggle on their own in court rather than providing effective training.

Case laws

The debate over judicial eligibility has essentially been a tug-of-war between academic brilliance and courtroom “grit.” Here is the shortened breakdown for your article:

- The 1993 Mandate: Experience First: In All India Judges Association, the Supreme Court initially made three years of practice mandatory. The philosophy was simple: you cannot effectively manage a courtroom without having “played the game” as a lawyer first. The Court believed that practical exposure to legal tactics was non-negotiable for anyone aspiring to the bench.

- The 2002 Shift: Chasing Talent: The Court later reversed its stance to prevent a “brain drain” to high-paying corporate firms. By allowing fresh graduates to join the judiciary immediately, they hoped to attract top-tier students who might otherwise skip litigation. For over two decades, the focus shifted from years on the floor to intensive institutional training.

- The 2023 MP Friction: The Grit Test: The tide turned when the Madhya Pradesh High Court introduced rules requiring either three years of practice or a stellar 70% academic record. While it caused significant legal friction, it sent a clear message: the higher judiciary felt fresh graduates often lacked the necessary temperament and practical “grit” required to handle the complexities of trial courts.

- The 2025 Restoration: A Middle Path: In May 2025, the Supreme Court officially restored the three-year practice requirement. However, it introduced a vital modern exception: time spent as a Law Clerk now counts as experience. This acknowledges that mentorship under a judge provides a unique, high-level perspective that bridges the gap between theory and practice.

Conclusion

The Three-Year Practice Rule has its pros and cons. It’s true that experience matters more for quality justice but sociologically, it risks making the judiciary elitist and inaccessible. The current junior advocacy ecosystem is exploitative and unregulated and therefore must be reformed.

The Path Ahead:

To make the rule succeed, these reforms must be implemented:

- Mandatory Stipend: Enforce minimum stipend for junior advocates.

- Revamp Training: Make judicial training practical.

- Support for Women: Offer scholarships and mentorship for female aspirants.

For aspirants in 2026: The path to the Red Beacon demands not just intelligence, but resilience. The climb is steeper, but the view from the top – earned through academic rigor and professional grind will be commanding.

Frequently Asked Questions

Has it become mandatory everywhere?

Yes, generally speaking. After the judgment in May of 2025, High Courts are revising their rules. However, this is prospective, which means if there was a notification for a job before this change in your state, you will probably still have to follow the old rules.

Does “Law Clerkship” count?

Yes! The Supreme Court itself has ruled that clerking for a Judge is deemed to be valid. It’s a good way to get the experience without the expense of practice.

When does the clock start ticking?

“Your 3 years start from the date of provisional enrollment with the State Bar Council.” You do not need to wait for the result of the AIBE before the “experience counter” starts ticking. Although you will need to pass the exam eventually.

Can I do an LLM at the same time?

Yes, but there is a catch. And you cannot be a full-time student. To keep your “active practice” status in force, you will have to stick to distance learning or evening classes.

What if I’m currently a Judicial Officer?

If you were appointed prior to May 20, 2025, and have completed three years in the position, you are exempt.