This article is written by Samriddha Ray, St. Xavier’s University, Kolkata

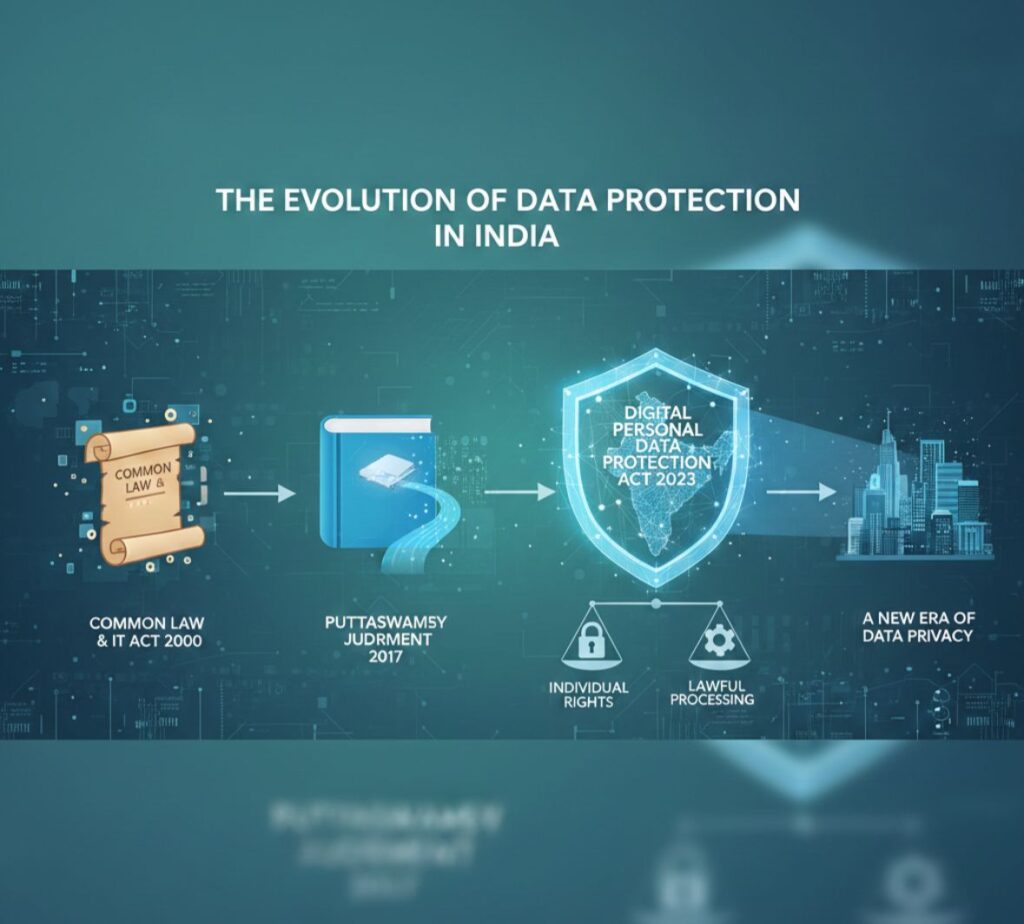

The rapid digitisation of public and private life in India has led to unprecedented volumes of personal data being collected, processed, monetised, and stored by governmental agencies, multinational corporations, and digital platforms. As technology has evolved, so have the risks to digital privacy: data breaches, unauthorised surveillance, social media profiling, algorithmic discrimination, identity theft, and misuse of sensitive personal information. For years, India lacked a comprehensive statutory framework that directly addressed personal data protection, relying primarily on the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) and the 2011 SPDI Rules. However, these provisions; limited in scope and ineffective against modern technological threats; necessitated a robust reform.

The enactment of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDP Act) marks a major legislative milestone, positioning India closer to the global standards established by the GDPR (European Union). The DPDP Act aims to balance individual privacy with legitimate state and business interests, creating a rights-based regime that governs how personal data must be collected, processed, stored, and shared.

This article examines the evolution of Indian data protection law, the key features of the DPDP Act, and significant judicial decisions shaping the contours of informational privacy, while assessing the practical challenges in implementation.

Case Laws

1. Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017)

The landmark nine-judge bench judgment recognised the Right to Privacy as a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution. The Court held that privacy includes autonomy over personal information, decisional privacy, and the right to control dissemination of personal data. The ruling laid the constitutional foundation for a future data protection law.

Key observations include:

- Informational privacy is integral to personal liberty.

- State surveillance must satisfy the tests of legality, necessity, and proportionality.

- Data collection must be accompanied by procedural safeguards.

This judgment served as the constitutional impetus for drafting the Personal Data Protection Bill, which eventually evolved into the DPDP Act.

2. Internet and Mobile Association of India v. Reserve Bank of India (2020)

Although this case primarily addressed cryptocurrency regulations, the Supreme Court emphasised principles relevant for data protection, including data minimisation and legitimate purpose in state regulatory actions. The judgment indirectly strengthened the argument that excessive or disproportionate data restrictions violate fundamental rights.

3. Canara Bank v. Union of India (2004)

In this pre-Puttaswamy judgment, the Supreme Court recognised privacy as an essential civil right, holding that unauthorised access to individual records by state authorities without procedural safeguards violates constitutional protections. The Court rejected the notion that information stored with banks or financial institutions automatically loses privacy protection.

The reasoning in this case foreshadowed later judicial views on data privacy and the need for strict safeguards governing data access and sharing.

4. Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020)

While dealing with internet shutdowns, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that restrictions on digital access must be lawful, proportionate, and accountable. The judgment also recognised that the digital sphere is protected by fundamental rights, including privacy and free expression. The proportionality standard applied in this case now informs the interpretation of lawful data processing under the DPDP Act.

5. K.S. Puttaswamy (Aadhaar), 2018 (Majority Judgment)

The Supreme Court upheld the Aadhaar scheme but struck down provisions enabling private entities to demand Aadhaar authentication. The Court held that data sharing must be backed by statutory authority, limited in scope, and proportionate to the purpose. This case highlighted the importance of purpose limitation, data minimisation, and explicit consent—central elements in the DPDP Act.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023: Key Features

1. Applicability and Scope

The Act governs:

- Personal data collected in digital form

- Offline data later digitised

- Personal data processed within or outside India if related to goods or services provided within the territory

It does not apply to personal data processed for personal/domestic use, publicly available data, or anonymised datasets.

2. Consent-Centric Framework

Consent forms the backbone of the DPDP regime. It must be:

- Free, informed, specific, unambiguous, and affirmative

- Accompanied by a clear notice

- Revocable at any time

Processing without consent is permitted only for “legitimate uses,” such as state functions, medical emergencies, or employment-related purposes.

3. Rights of Data Principals

The Act grants individuals several enforceable rights, including:

- Right to access information about personal data processing

- Right to correction and erasure

- Right to grievance redressal

- Right to nominate a representative in case of death or incapacity

These rights indicate a significant shift toward user autonomy.

4. Duties of Data Fiduciaries

Entities processing personal data must:

- Implement reasonable security safeguards

- Notify data breaches to individuals and the Data Board

- Maintain accuracy and integrity of data

- Delete data once the purpose is fulfilled

- Appoint a Data Protection Officer (for Significant Data Fiduciaries)

5. Data Protection Board of India

A quasi-judicial body empowered to:

- Enforce compliance

- Investigate breaches

- Impose penalties

- Issue directions

Its role is crucial to operationalising the Act.

6. Cross-Border Data Transfers

Unlike previous drafts, the DPDP Act adopts a blacklist model—data may be transferred outside India except to countries explicitly restricted by the government.

This flexibility supports global data flows while retaining state regulatory control.

7. Penalties and Enforcement

The Act introduces hefty monetary penalties, including:

- Up to ₹250 crore for data breaches

- Up to ₹200 crore for non-compliance with duties

- Up to ₹50 crore for failing to notify breaches

The penalty system mirrors international best practices and reflects India’s intention to build a competitive digital ecosystem.

Practical Challenges and Concerns

1. Broad Government Exemptions

Critics argue that the Act provides the State with wide discretionary powers to exempt governmental agencies from compliance. This may compromise the privacy protections envisioned in Puttaswamy.

2. Limited Protections for Children’s Data

The Act requires parental consent for minors but does not address issues of:

- EdTech surveillance

- Targeted content

- Profiling

- Algorithmic manipulation

A more detailed regulatory framework may be required.

3. Absence of ‘Sensitive Personal Data’ Classification

Unlike the earlier draft, the DPDP Act does not categorise sensitive data separately, potentially reducing safeguards for health, biometric, financial, or genetic data.

4. Implementation Capacity

Effective enforcement depends on:

- Skilled personnel

- Adequate funding

- Efficient grievance mechanisms

- Industry readiness

The transition may be challenging for MSMEs and emerging tech platforms.

Conclusion

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 marks a transformative shift in India’s digital governance framework. For the first time, individuals have enforceable rights over their personal data, and entities processing data must adhere to strict compliance standards. While the Act brings India closer to international norms, concerns remain regarding state exemptions, minors’ data, and enforcement capacity.

Nevertheless, the DPDP Act lays the groundwork for a future-proof legal ecosystem that balances privacy, innovation, and national security. As jurisprudence evolves and new regulatory rules are framed, India’s data protection landscape will continue to mature, shaping how citizens, corporations, and the State navigate informational privacy in the digital age.

FAQs

1. What is the main objective of the DPDP Act, 2023?

Its primary objective is to regulate the collection, storage, and processing of personal data while ensuring individual privacy and promoting responsible data practices among organisations.

2. Who is a Data Fiduciary under the Act?

A Data Fiduciary is any entity; governmental or private; that determines the purpose and means of processing personal data.

3. What rights does an individual have under the Act?

Individuals have the right to information, right to correction, right to erasure, right to grievance redressal, and right to nominate a representative.

4. Does the Act allow transfer of personal data outside India?

Yes. Personal data may be transferred to any country except those specifically restricted by the Central Government.

5. What are the penalties for violations?

Penalties range up to ₹250 crore for data breaches, ₹200 crore for non-compliance, and ₹50 crore for failure to notify breaches.

References

Supreme Court Judgments / Case Laws

1. Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017) – Right to Privacy Judgment

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/127517806

2. Internet and Mobile Association of India v. Reserve Bank of India (2020)

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/184654597

3. Canara Bank v. Union of India (2004)

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/563754

4. Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020)

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/167985262

5. K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (Aadhaar Judgment) (2018)

Majority Judgment

https://indiankanoon.org/doc/127517806/

6. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 – Full Text (Official Gazette)

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.meity.gov.in/static/uploads/2024/06/2bf1f0e9f04e6fb4f8fef35e82c42aa5.pdf

7. PRS Legislative Research – DPDP Act Summary & Analysis

https://prsindia.org/billtrack/digital-personal-data-protection-bill-2023

8. Information Technology Act, 2000 (Bare Act – MeitY)

https://www.meity.gov.in/content/information-technology-act-2000

9. IT (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011

https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/GSR313E_10511%281%29.pdf

10. OECD Principles on Privacy (International Reference)

https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/privacy-and-data-protection.html